In this extremely comprehensive guide to standby letters of credit (SBLC), we cover:

- What a standby letter of credit is

- Why SBLCs are used more commonly in the USA

- Risks and considerations to be aware of when using standby letters of credit

- An overview of the different types of SBLC available

- The differences between SBLCs and other similar instruments including demand guarantees

- The rules and regulations you need to know about when using standby letters of credit

The guide is written by Glenn Ransier, Technical Advisor, ICC Banking Commission and the Head of Documentary Trade and Standby LCs with Wells Fargo Bank in North America.

Let's get started. (Note this is a long guide, if you'd rather download the PDF version to read later, you can do so here)

What is a Standby Letter of Credit?

The global rule sets which govern standby letters of credit (SBLC) - both the Uniform Customs and Practices current revision 600 (UCP 600) and International Standby Practices current revision (ISP98) - define a SBLC as an “undertaking”. An undertaking provides the named beneficiary with an “independent” assurance of payment from the undertaking’s issuer (issuers are most often banks).

The obligations of the SBLC or “undertaking” supplement, and are in addition to, any other underlying contract/agreement between the issuer’s client (In SBLC terms, the client is most often referred to as the applicant) and the client’s contract counterparty (In SBLC terms, the counterparty is known as the beneficiary).

When the issuer bears a stronger credit rating, a SBLC is also a credit enhancement tool. An applicant’s ability to obtain a SBLC from an issuer reflects good faith as the SBLC supports an applicant’s credit quality.

In most cases and depending on the nature of the type of SBLC being issued, a beneficiary is typically only authorized to claim payment from an issuer in situations where the applicant is unable to successfully conclude the underlying contract.

While a SBLC may include a reference to an underlying contract between an applicant and a beneficiary; the issuer’s obligations remain fully independent of any underlying contract to which it may be supporting.

As an independent undertaking, the issuer of the SBLC has its own obligation to ultimately pay the beneficiary (or another bank which has already paid the beneficiary such as a confirming bank) on receipt of a document/presentation made by, or on behalf of the beneficiary, which comply with the terms and conditions of the SBLC.

However, most SBLCs never receive a drawing, (also known as: claim or demand for payment) and simply expire in accordance with a SBLC’s stated expiry date/period. This is because most applicants will successfully complete their contractual obligations and as such, the beneficiary will have no reason to demand payment under a SBLC. Upon a standby letter of credit’s expiry, it will simply cease to exist and be unavailable for drawing and closed by the issuer.

Unless otherwise stated in a SBLC, standby letters of credit are deemed: “irrevocable” meaning they cannot be changed or cancelled prior to its stated expiry date without the agreement of all parties.

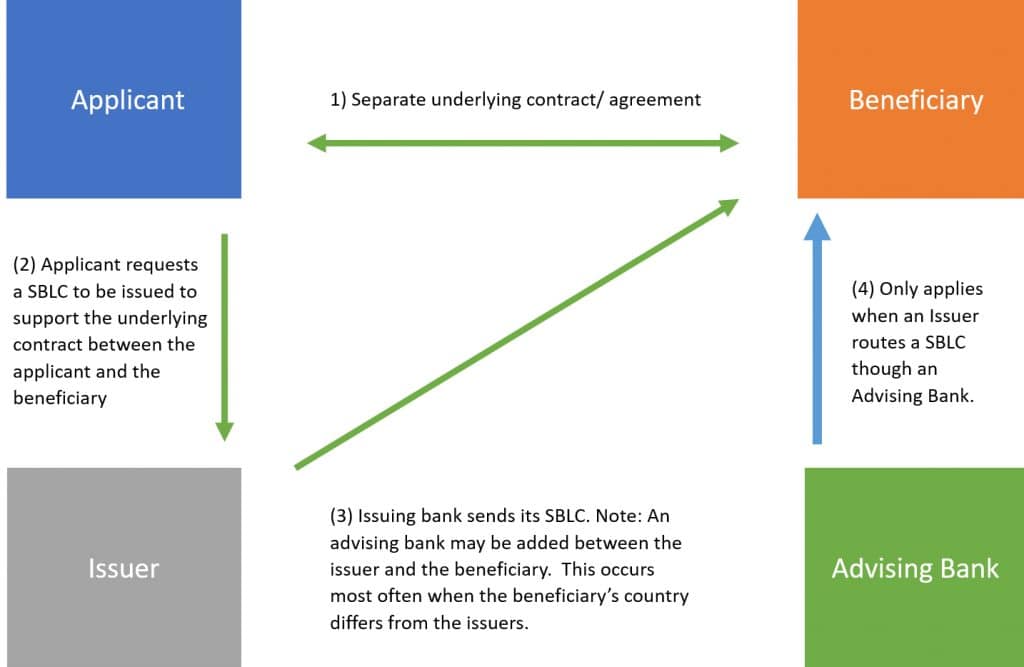

Example of a typical process flow for a SBLC

SBLC issuance process – direct to beneficiary or utilizing an advising bank

Benefits of using SBLCs

- A bank’s SBLC substitutes and may enhance or replace the creditworthiness of the applicant for that of the issuer of the standby letter of credit.

- SBLC undertakings support/collateralize “any” type of underlying contract, agreement, or obligation between an issuer’s client/applicant and the applicant’s client/counterparty, the beneficiary.

- SBLCs are recognized globally as an effective means of securing cross-border and domestic contracts.

How are SBLCs commonly used?

Banks following BASEL or Dodd-Frank requirements will classify their issued or confirmed SBLCs as supporting either a “financial” or a “performance” obligation. These two classifications are defined as:

- “Financial” SBLCs are issued to back financial obligation or some form of indebtedness, such as loan repayment, and irrevocably obligate the Issuer in the event the Applicant fails to honor their payment obligation.

- “Performance” SBLCs are issued to back a company’s performance related duties. These are contractual, non-financial obligations such as: completing the building of a road or wind farm, etc. and irrevocably obligate the Issuer in the event the Applicant fails to perform as agreed.

Who are the parties involved in a Standby Letter of Credit?

Advising bank –The beneficiary will typically request that a SBLC is sent to a bank in their country or one with which the beneficiary has a relationship. If the beneficiary does not request a specific bank, the issuing bank will either: send the SBLC directly to the beneficiary or choose to send the SBLC to the beneficiary through a bank with which the issuer has a relationship.

If the issuer sends the standby letter of credit through another bank, the bank that receives the SBLC and sends it to the beneficiary will be known as the advising bank. The advising bank is not a party to a SBLC and has no authority to approve or disapprove an amendments terms or obtain drawing rights.

Applicant - (also known as an instructing party or requesting party) – The SBLC applicant enters into a contract with a counterparty. When the contract requires a standby letter of credit to support it, the applicant will make a request, typically to its bank, to issue a SBLC in favour of its contract’s counterparty. In SBLC terms, the counterparty becomes the beneficiary.

In the underlying contract, the applicant and beneficiary terms associated with SBLCs may have very different names: e.g. lender and borrower; buyer or seller; principal and drawer; etc.

It must be noted that a SBLC’s stated applicant may or may not be the issuer’s client. An applicant may receive silent or openly known support to have a standby letter or credit issued. For example, Company AZA may have insufficient credit or collateral to induce an issuer/bank to issue its SBLC. In such a case, it can enlist its parent, a factoring company, etc. to lend support to help Company AZA be named as the applicant in the SBLC.

The parent or other company providing the support may or may not be stated in the SBLC; however, it is considered the client/applicant of the issuer versus the applicant stated in a SBLC. An applicant is not deemed a party to an SBLC. They are the party which requests an issuer to issue its independent SBLC in favour of a beneficiary.

Beneficiary – is the undertaking party who receives all the benefits of a SBLC. They are the only party who may make a drawing; receive payment against the SBLC and/or accept or reject amendments, etc. In the underlying contract, the applicant and beneficiary terms associated with SBLCs may have very different names: e.g. lender and borrower; buyer or seller; principal and drawer; etc.

Confirmer or Confirming Bank –confirmation may only be added at the request of an issuer. When added, a confirmer or confirming bank becomes similar to a second issuing bank because, like the issuer, the confirmer undertakes to honour (or negotiate) or pay a complying document presentation. The confirmer’s undertaking is in addition to the issuers undertaking, but it may be limited in several manners, such as: a) amount; b) expiry; and c) allowable languages documents may be presented in, etc.

Issuer or Issuing Bank or Opening Bank – is the party that issues a separate, irrevocable, independent SBLC on behalf of its applicant client. Because it is independent, a SBLC is separate and distinct from any underlying contract on which it may have been based. Because it is irrevocable, a SBLC cannot be amended until all parties agree to the amendment.

Nominated Bank is the bank/party authorized by the issuer to undertake honour, negotiate or otherwise make a payment in the event it receives a complying document presentation/demand. A confirmer is most often a nominated bank.

A nominated bank which has not confirmed or otherwise committed to pay in some form has no obligation to do so. Unless a confirmer is involved in a SBLC, it rare to see a nominated party as the majority of SBLCs expire and are only available for payment with the issuer.

Why are SBLCs more commonly used in the United States?

Banks in the U.S. historically did not have the corporate power to issue certain types of guarantees but have generally always had the power to issue letters of credit (LC).

It was relatively simple to take conventional commercial LCs and adjust the drawing conditions to call for documents like default certificates and demands for payment, rather than on board negotiable bills of lading, invoices, and other typical shipping and commercial documents. This meant SBLCs could evolve from commercial LCs. It is harder to convert an ordinary, dependent guarantee into an independent undertaking.

Risks and considerations to be aware of when using SBLCs

Applicant considerations:

There is a cost associated with SBLC transactions.

An applicant is not a party to an SBLC. The applicant is a party to an underlying contract while the issuer of the standby letter of credit is not. The applicant requests a SBLC to be issued. However, once issued, the issuer must then make its own, independent examination and payment decisions independent of input from the applicant and what the terms of an underlying contract state.

An applicant should have a relationship comfort with the intended SBLC beneficiary because most standby letters of credit are payable against only a draft/bill of exchange and a simple drawing statement. This allows for the possibility for an improper drawing.

Once a SBLC is issued, all parties must agree to any amendment or cancellation request unless the SBLC has expired.

Applicants must align the contract’s terms with the SBLC especially in the area of drawing requirements. Because a standby letter of credit is documentary, an issuer is not concerned with the underlying contract and will make its payment decision solely upon reviewing a beneficiary’s document presentation on its face, against an SBLCs terms, without seeking confirmation of fact(s), action(s) or statement(s) made by the issuer of any document contained in the presentation.

Beneficiary considerations:

A beneficiary must determine its credit rating of the issuer. Where an issuer’s credit rating, size or country risks are unacceptable to the beneficiary, a beneficiary may require an acceptable confirming bank.

Once the beneficiary receives a SBLC, it should ensure that SBLC wording complies with the requirements of the underlying contract e.g.

- Can a beneficiary legally make the required statements and are all reasons they can make a demand for payment properly addressed?

- Does the SBLC expire with sufficient time to complete the underlying contract?

- Can the beneficiary obtain all required drawing documents?

This upfront review will help to assure success if the beneficiary makes a drawing against the SBLC, understanding that when a presentation does not comply with a SBLC’s stated terms/conditions, an issuer is not obligated to pay.

The SBLC should be made subject to its preferred international rules such as ISP98 versus UCP600 as the rules align everyone involved with a SBLC and may also assist in the case of a legal matter.

Confirmation and/or advising costs may be due by the beneficiary.

Issuer considerations:

As the issuer is supporting its applicant, it needs to consider the applicant’s credit rating. They also need to consider their ability to complete the underlying contract/agreement, often without reviewing the contract/agreement.

Reputational and/or compliance risks such as money laundering, collusion between an applicant and a beneficiary, supporting an unpopular contract/agreement, etc. should also be considered.

Types of SBLC

Here is an overview of the most common types of SBLC.

This SBLC’s purpose is to ensure the repayment of an advance payment which a buyer has made (or will make at a contract’s closing) to the supplier of goods or services.

In connection with large contracts, especially international transactions, the parties will agree that a supplier of goods or services must receive a certain percentage of the overall contracted value, e.g. 10% upon signing of the contract. To safeguard the buyer against losing its advance payment, they will require an SBLC naming them as the beneficiary to secure the repayment of the sum(s) advanced should the contracted goods or services not be delivered or completed.

The SBLC ensures the buyer is made whole for any advance made. However, often these types of SBLC’s do not provide remuneration for any loss of interest or profit margins that the buyer may sustain.

Supports an issuers' client’s bid to be awarded for a project or contract mandate. This type of SBLC assures the beneficiary that if selected, the applicant has the ability to support and comply with its bid and that they will honour the bid if they are selected. Most often used by contractors or construction companies, they are typically needed for a portion of the overall project’s value.

A SBLC which generally requires only the presentation of a draft or bill of exchange without the need of any supporting statements whatsoever. From an applicant and/or an issuers perspective, these are considered the riskiest type of SBLC. This is because a beneficiary will be able to draw for any reason. It is also risky because the simple terms of the SBLC with regards to a presentation or drawing requirement makes it difficult to stop an improper drawing.

Supports an applicant’s payment obligations to pay for goods or services on a one-off or ongoing basis in the event of non-payment by other methods.

Direct Pay LCs are hybrid SBLCs issued to provide a credit enhancement to a bond offering. E.g. industrial revenue bond, also commonly referred to as variable rate demand bonds. These types of SBLC are most often issued in favour of the bond trustee. Unlike the majority of SBLCs, they are the primary payment mechanism for the interest and principal due on the underlying bond and will receive periodic drawings for payment.

A large majority of SBLCs will fall into this category. These standby letters of credit will support any financial payment obligation such as loan repayments, etc.

These SBLCs address the insurance or reinsurance obligations of the applicant and are used by insurance companies to distribute insurance risks among themselves. Rather than cash collateralizing other insurers or beneficiaries for use of their internal lines of credit, these SBLC’s are used as collateral.

A performance SBLC is used to secure the applicant’s satisfactory fulfilment of its contractual performance obligations toward the beneficiary. For example, should the applicant fail to perform a contracted duty such as: complete a construction project, or repair equipment, or build a home or road within the contracted specifications and/or timelines, then the beneficiary will be entitled to present a drawing statement.

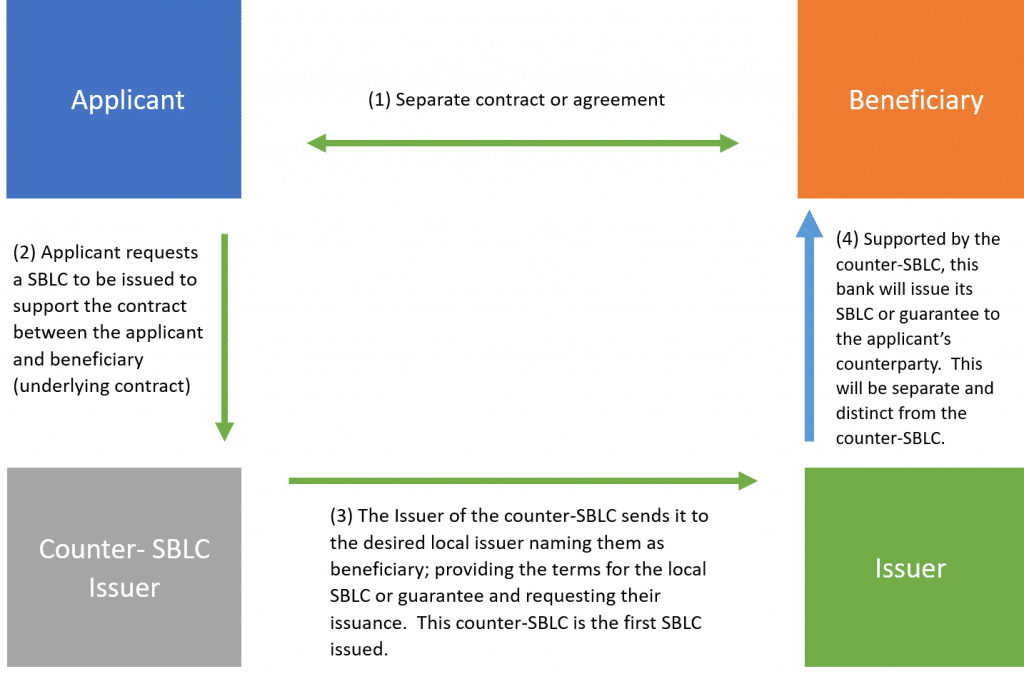

An applicant or the beneficiary may require a local SBLC to be issued directly by an overseas, reputable party - most often a bank - in the same country as the beneficiary.

The applicant may not have the means or would prefer not to open another line of credit with an overseas party to facilitate this limited need. In this case, they would request an issuer to issue a counter SBLC. The counter SBLC provides collateral to a local party or bank (often a correspondent of the issuer of the counter-undertaking), to induce that bank to issue its own separate and distinct, local undertaking.

In these instances, there are two undertakings:

- The 1st is the counter-SBLC between the issuer and the local bank

- The 2nd is the local undertaking between the local issuer and the beneficiary

The undertaking type and/or their governing rule sets do not need to be like for like. Each bank has its own policies toward issuing and receiving counter SBLCs.

Through the use of counter SBLCs, a client maintains a single line of credit.

A counter SBLC may be necessary in the following scenarios:

- Beneficiary requires/demands a local SBLC or guarantee;

- Beneficiary requires a “local bank” to issue the final undertaking and will not allow another local bank to advise or confirm it;

- The undertaking or guarantee must be subject to laws outside of the issuer’s policies.

The beneficiary of the counter-SBLC is the financial institution requested to issue its own instrument. The beneficiary of the second instrument is the applicant’s counterparty in the underlying contract/agreement.

The drawing requirements for a counter-SBLC generally require a simple statement that the second financial institution received a demand for payment against the instrument it issued. The drawing requirements under the second instrument will have ultimately been provided by the applicant of the counter SBLC issuer.

Example of a typical process flow for a counter SBLC

What is the difference between an SBLC and a Commercial Lettter of Credit?

Costs – Costs between SBLCs and Commercial LCs usually differ.

At a high level both types of LC typically require an issuer to consider factors such as:

- Applicant/client size

- Collateral and required line of credit size

- The issuer’s internal LC processing costs

- Credit establishment and compliance risk costs

- The differences of the types of LCs anticipated to be requested

Depending on the laws applicable to the Issuer, there may be different cash reserve loss requirements needed for commercial LCs vs performance SBLCs vs financial SBLCs, (Note: This is the case for all countries following Basel) which may affect the issuing/opening fee.

Both LC types will require an applicant to pay an issuance fee of some type. However, commercial LCs are expected to have at least one, if not multiple document presentations. Each presentation will typically be assessed by an examination fee of some type. Conversely, most SBLCs do not receive a beneficiary’s document presentation or drawing and so no examination related fees will be assessed.

Where a SBLC generally covers longer term and ongoing contracts, the issuance fee is needed for the duration of the SBLC.

Commercial LCs are typically issued to support a single need e.g. to cover a payment for: a) a shipment of goods; or b) services completed. They typically expire earlier than a SBLC.

For applicants and beneficiaries which routinely transact, a longer term SBLC may be the more economical LC undertaking, instead of issuing multiple commercial LCs. The commercial LCs will be assessed multiple issuance and examination fees.

Document presentations – Commercial LCs are a beneficiary’s primary payment option. Rather than relying on the underlying contract for payment, the beneficiary will request payment from the issuer’s independent commercial LC undertaking in settlement of the underlying contract they have with the applicant. Conversely, SBLCs take the opposite view and, in the overwhelming majority of cases, the issuer of a SBLC does not expect to receive a document presentation nor make a payment.

As a secondary payment option to the beneficiary, if a document presentation/demand is received, it generally means that the applicant has failed to meet its terms against the underlying contract.

Document types – Commercial LCs require documentary presentations which usually consist of commercial documents such as commercial invoices, packing or weight lists, transport documents, etc. SBLCs are payable most often against simple beneficiary statements and the documents presented often have no intrinsic value.

Misstatements/Fraud – Understanding the difference with document types outlined above, the possibility of a beneficiary requesting a payment in error, by accident or purposely are greater with a SBLC. While a very rare occurrence, it is recommended that the applicant and beneficiary have an established relationship when dealing with SBLCs.

Duration - Commercial LCs are typically short term in nature and their expiry date is generally 6 months or less. SBLCs most often cover longer term contracts, and their duration may be years in length on an overall basis.

Tenors – Any LC undertaking must define the period when a complying document presentation is due for payment and this period is known as the LC’s tenor. As LC undertakings, both Commercial LCs and SBLC’s can be payable “at sight”. This means upon a reasonable time from when the nominated or issuer has found the documents to comply with an LC’s terms.

Conversely there also exists time tenors, which detail that a payment is to be made at a fixed future certain date from the time a presentation is found to be complying. Time tenors are typically referred to as Deferred Payment Undertakings or Banker’s Acceptances. One term, “Negotiation”, may be used as a sight or time tenor.

Commercial LCs often include some form of financing need for trade and, as such, time tenors are utilized. SBLCs which generally do not expect a presentation or demand for payment will overwhelmingly use the sight tenor.

Terms and Conditions – Given their very different payment needs, the data content of commercial versus SBLCs differs significantly.

Purpose – Commercial LCs facilitate trade and are issued with the intention that a document presentation will be delivered to a bank for payment for a shipment of goods or payment for services. They are the primary payment vehicle for the beneficiary.

On the other hand, SBLCs cover any type of contract or agreement between two parties. Provided the issuer is willing to support its applicant, the type of contract a SBLC can support is boundless and includes the different types we covered above (which is not an exhaustive list).

When an applicant does not meet its contracted duty(ies), the beneficiary will make a claim against the applicant for payment under the underlying contract. When the applicant fails to honour the request for payment, the beneficiary will make a presentation for payment against the SBLC making it a secondary payment vehicle, or payment of last resort for a beneficiary.

SBLCs vs Bank Guarantees

Similar to the commercial LC or a SBLC, a demand guarantee (DG) is an independent and irrevocable “undertaking,” provided by an issuer to a beneficiary, that provides assurance of payment upon receipt of complying document presentations.

DGs are often referred to as first demand guarantees. DGs are more common in Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. SBLCs are more common in the Americas, however they remain globally issued and/or accepted.

Surety or ancillary guarantees should not be confused with DGs and are not the same as LC undertakings. They are outside the scope of this guide.

DGs and SBLCs are extremely similar “undertakings” with the key differences provided by its governing rule set. Like the SBLC, demand guarantees:

- Require the beneficiary to present a compliant documentary demand in order to receive payment against the undertaking

- Are independent from the underlying contract

- Do not require the issuer to investigate the legitimacy of a demand.

When included in a SBLC, UCP600 or ISP98 will govern the instrument and provide a series of default resolutions in cases where a SBLC is silent. Conversely, when included in a DG, the Uniform Rules for Demand Guarantees (URDG 758) will govern and provides it defaults resolutions.

While some defaults are similar, there are significant differences in the approach taken by the rule sets especially in areas such as:

- Force Majeure situations

- Document examination period and approach

- Confirmation

- Allowable payment tenors

- Required notifications to an applicant

- Governing law and jurisdiction

- Replacing a DG or SBLC undertaking lost by a beneficiary

- Some terminology differences e.g. guarantor versus issuing party.

Most banks will require a DG to be subject to the URDG 758 to normalize the roles and responsibilities of each party to the undertaking. Issuing a DG that is silent as to its governing rule set and/or is subject to laws of another country, creates potential risk for the issuer (guarantor is the issuer for DGs) and the applicant. This is because the roles and responsibilities may not be directly addressed, well known or understood.

SBLC rules and regulations

Below is an overview of the key regulations, codes and rules that govern SBLCs.

International Standby Practice (ISP98)

- ISP is a set of rules that when incorporated into an undertaking by referencing the ISP98 or ICC publication 590, will cause the undertaking to be deemed as a Standby Letter of Credit.

- The ISP was approved and endorsed by the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) in January 1999 (ICC publication 590).

- The ISP took more than five years to create and it was the result of interaction between individuals, banks, and national and international associations.

- The ISP98 is a copyright of the Institute of International Banking Law & Practice (IIBLP).

- ISP is not law, but it contains resemblances to USA L/C legal doctrine.

- It represents a more comprehensive rule set for SBLCs versus the UCP 600.

Uniform Customs and Practice (UCP 600)

- UCP is a set of rules that that when incorporated into an undertaking, will

cause the undertaking to be deemed as a letter of credit. - The primary focus of the UCP is to govern commercial letters of credit. However, as noted in UCP Article 1 in parenthesis, UCP applies to standby letters of credit “to the extent to which they are applicable”.

- UCP is not a law, rather a set of articles developed by the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) Banking Commission and others. They are copyrighted by the ICC

- ICC is a non-governmental organization.

- UCP was first published in 1933 making it the oldest and most legally tested rule set. Thereafter revised in 1951, 1962, 1974, 1983, 1993 and its current revision in 2007.

- UCP is not as thorough on SBLC day-to-day practice. It does not address a variety of situations such as:

- Receiving a document presentation which contains an extend or pay request e.g. request to extend the expiration date of the SBLC or pay the presentation

- Issuances of counter-SBLCs;

- Examining documents against a SBLC which requires a document to make and/or complete a statement utilizing quotation marks; require a witness, etc.

- What to do in cases where a beneficiary has merged or been acquired after issuance of an SBLC

- Syndicated or participated deals.

Uniform Rules for Demand Guarantees (URDG 758)

- The URDG is a set of rules that that when incorporated into an undertaking, will cause the undertaking to be deemed a demand guarantee (DG).

- URDG 758 entered into effect July 2010 and is a complete revision of the original revision URDG 458.

- The URDG rules support demand guarantees, not surety guarantees.

- Where possible, it was aligned with the concepts of UCP 600; however, its default positions differ from UCP and ISP in a variety of manners.

- URDG 758 now has a companion document titled the International Standard Demand Guarantee Practice (ISDGP) for URDG 758 (ICC publication 814E). It supplements the URDG by identifying and recording best practice in relation to the URDG rules and beyond.

Evergreen clauses

Given the long-term expiry nature of SBLCs, they often insert what is commonly referred to as an “Evergreen” or “automatic-extension” clause. The Evergreen Clause allows an SBLC’s expiry date to automatically extend for a fixed period-of-time (e.g. every six months or year).

It also provides an issuer or confirmer and/or the applicant with an exit period (e.g. “unless XX days prior to any then current expiration date, the issuer notifies the beneficiary that the issuer elects not to extend the SBLC”). This allows them the possibility to have the SBLC expiry with a simple cancellation notification and without the need for a beneficiary to agree to an amendment.

However, any cancellation notification must be sent or received by the beneficiary by the notification period indicated in the SBLC’s specific evergreen clause. This is normally anywhere between 30 and 90 days from a then current expiration date.

How Evergreen clauses benefit SBLCs

The applicant, issuer or confirmer is provided with the means to close the SBLC without the need for a beneficiary to consent or otherwise have to agree to an amendment or return an undertaking. (Note: The cancellation is typically sent when the underlying contract is also close to completion, but there remain other reasons for cancellation such as: applicant seeking to replace an issuer for improved costs or other reasons, or an issuer seeking to remove itself from a deal; etc.)

In addition, providing longer-term commitments often requires higher rates/fees. The exit opportunity provided by an Evergreen Clause may keep fees more reasonable.

SBLC frequently asked questions

About the author

Glenn Ransier

Technical Advisor, ICC Banking Commission; Member of URDG 758 drafting team; and Co-Chair for the ISDGP

Head of Documentary Trade and Standby LCs with Wells Fargo Bank N.A.

Email: glennransier@yahoo.com

Disclaimer: Contents represent the author’s sole opinions and may not represent those of any past, present or future employer.