On 23–29 March 2021, MS Ever Given was stuck abeam between the banks of the Suez Canal and consequently blocking almost 400 other vessels´ navigation northbound or southbound.

After a salvage operation including 11 tug boats and two dredgers and some 800 Egyptian workers, the vessel could resume her voyage - but not far. The vessel found herself in the Great Bitter Lake in the middle of the Suez Canal and was arrested by the Egyptian authorities. The Suez Canal Authority (SCA) placed a claim of allegedly USD 916 million against the shipowners, Shoe Kishen Kaisha.

After fiery legal battles and concurrent negotiations, the vessel finally free to resume its journey on Wednesday, 7 July, after 106 days of being first stuck and then detained by authorities. The conditions for the release have not been disclosed so that neither party would lose its reputation, but some guesses can be made from what has been reported so far.

The amount of the claim was gigantic as it has been estimated to exceed the aggregate value of the ship and cargo. A similar incident occured in 2018 when MS Maersk Honam caught fire in the Red Sea. It was reported that the total values at stake (consisting of the ship and cargo) in the 2018 tragedy, were a little over USD 500 million. We can use this as a measurement stick with MS Ever Given, too.

The breakdown of the amount claimed by the SCA reportedly included salvage charges that consist of direct costs as well as a substantial salvage bonus and liability for loss of reputation. Egyptian courts were seized for arrest actions. The shipowner and the charterer Evergreen Shipping Ltd. filed for jurisdiction of English courts, which is typical as English law governs many or most contracts of affreightment.

The shipowner filed a limitation of liability claim before the English Admiralty Court on the basis of the 1996 Protocol of the 1976 Convention on Limitation of Liability for Maritime Claims. It has been estimated that the amount of the limitation fund would be USD 114 million.

The problem here was that the SCA claimed an amount that was exorbitant. Who could pay such a sum and on what basis? As the claim included damages for the loss of revenue and reputation for the SCA, this would mean invoking shipowners´ liability covered by the liability insurer, the UK P & I (protection and indemnity) Club. There was a problem, however, that P & I clubs are like other liability insurers that they would not pay in excess of the legal liability of the policyholder. Egypt has ratified the Limitation of Liability Convention referred to above.

Another way the problem has been approached is to look at sharing the claims between the shipowners and other interests caught, most notably the cargo interests. The vessel and cargo were salved by the SCA, and international legal rules on salvage give the salvors a substantial remuneration in proportion to salved value. This remuneration is also called salvage.

It was reported that the SCA claimed - on the basis of the applicable Suez Canal Agreement - substantial direct operation costs plus a salvage bonus of possibly USD 300 million. This would account for probably more than half of the salved value. There are many other costs incurred by the shipowners in the first place, which are to be divided between the ship and cargo.

For this purpose, the shipowner has declared general average. General average is a situation where both the ship and its cargo (sometimes also freight or bunkers) are in peril due to grounding, fire on board or another reason, and expenditures have to be incurred or sacrifices made to save them or minimize the loss.

This is a very old legal institution as it has already been referred to in the Justinian codification of Roman law and you can find examples of general average acts in the Bible! See Acts of Apostles, Ch. 27, 18–19:

”18 We were being pounded by the storm so violently that the next day they jettisoned some cargo,

19 and on the third day with their own hands they threw even the ship’s tackle overboard.”

Salvage may be included in general average but may be a system in its own right. In both general average and salvage the cargo interests, those bearing the risk for the loss of or damage to the goods according to Incoterms® 2020, must contribute to costs involved. Therefore the claim may be partly paid by the cargo insurers and partly by the hull and machinery (H & M) insurers of the vessel to the extent salvage and other expenses falling under general average are concerned.

As far as shipowner´s liability is concerned, the UK P & I Club shall pay on behalf of the shipowners.

It has been reported by press that in settlement negotiations running in parallel between the SCA and the owners and their insurers, the SCA would have accepted a lower sum of around USD 550 million out of which USD 200 million should be paid upfront.However, the owners and the UK P & I Club have offered USD 150 million.

We do not know as of today what the breakdown between shipowners´ liability and salvage and other costs falling under general average are. It is probable that the shipowners have been in contact with the major cargo intrests and their insurers.

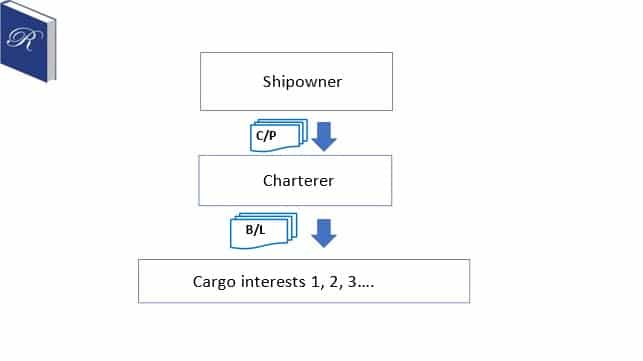

Shipping contracts are often contractual chains, which must be taken into consideration. In this case, the shipowners are Japanese, Shoe Kishen Kaisha Ltd. but the ship is chartered by a charterparty (C/P) to the Taiwanese Evergeen Shipping Ltd (Evergreen). I undrstand that Evergeen has issued transport documents, probably bills of lading (B/L) to the shippers of the goods in some 18.000 containers on board. The bills have probably switched holders, often pursuant to presentation under documentary credits.

As the ship´s insurers will so far have paid (or guaranteed) the sums to the SCA, there may arise disputes as to the legitimacy of the expenditures, but this should normally not be a concern for the cargo interests, who are usually the consignees or shippers of the cargo, depending on the the trade term referred to in the sales contract, based mostly on Incoterms® 2020.

In international trade, cargo insurance is most often procured applying the Institute Cargo Clauses (I.C.C.). There are three variants of these Clauses:

- Clauses A covering all risks unless specifically excluded

- Clauses B being a rarely used ´halfway-house´ between extended and restrictive clauses

- Clauses C being only applied in listed perils when something happens to the means of transport such as the sinking of the ship or derailment of a land conveyance.

As we know, Incoterms® 2020 introduced a change whereby the CIP (Carriage and Insurance Paid to) seller must procure insurance based on the I.C.C. Clauses A or equivalent, whereas a CIF seller still must procure only on the I.C.C. Clauses C. There are special mentions on the war risks and strike risks insurances. Cargo insurers also offer other additional insurances e.g. for frozen foods.

The good news is that all these variable Clauses cover contributions to salvage and general average. Cargo insurers also issue guarantees to facilitate the release of the goods to the consignee so that the shipowners or carriers do not resort to liens to force payment.

We should recall that insuring is not a must with the other Incoterms® rules, other than CIP and CIF. Should you not have insured, the only way for the consignee to gain delivery is that someone places a cash deposit to the shipowners. As the probable salvage charges may be well over half of the value of the goods, this alternative may not be very appealing.

In the end, it is the cargo interests, and especially those not strong and powerful, to suffer from the situation. Also consignees and shippers of goods on board of the other vessels, which MS Ever Given blocked from passing the Suez Canal, suffered from delays. The liability of the carriers is limited and it may be difficult to establish liability for delay as no time commitments are usually made by carriers.

Cargo insurance based on the Institute Clauses does not cover damage attributable to delay in any manner. Moreover, cargo interests may be affected by claims for demurrage or detention for occupying containers for too long. This is not covered by any insurance. However, business interruption policies, where applicable, may protect the cargo interests.

The incident inevitably calls for traders to recognize that on top of the risks of loss of or damage to the goods, which are addressed both in the United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (CISG) and in Incoterms® 2020, there exists the risk of delay. This risk has already been recognized in case law on the CISG.

Risk should be distinguished from liability, which is addressed by standard contract terms such as liquidated damages clauses. Risk means bearing the adverse (usually) economic consequences of an incident. Liability means compensating the loss someone else suffers.

The Suez Canal is the route for the shipments between Europe and Asia and also to America. Its blockage contributed to the rising freight and container rates that have already soared during the COVID-19 pandemic. Contracting for carriage (or taking care of the transport by your own means, which incoterms® 2020 now expressly allows) is much more costly and risky.

We may recall that FCA, FAS and FOB Incoterms® 2020 recognize the possibility for the seller and buyer to agree that the seller contracts for carriage at the risk and expense of the buyer. This risk means something else to that of loss or damage to the goods or, for that matter, the risk of delay. It means the risk availability of transport facilities and the ensuing price increase caused by shortages.

The SCA is considering widening the Suez Canal in the place of the stranding of MS Ever Given to avoid a similar thing happening again. This incident may nevertheless open many people's eyes to consider what else can be done to improve the contractual insfrastructure in which trade takes place.

About the author

Dr. Lauri Railas

Attorney-at-Law, Railas Attorneys Ltd.

Adjunct Professor of Civil Law, University of Helsinki

The Average Adjuster in Finland

Active in the ICC since 1991: Secretary General of ICC Finland 1991–96. Active in the CLP Commission also thereafter. Member of a number of CLP working groups, including the Drafting Group for Incoterms®2010). Contributed also the ICC Guidebook on Transport and the Incoterms® 2020 Rules.

Please note this is an opinion piece and Dr. Railas’ views do not represent the views of ICC or the ICC Academy.